Equipped with mental models, Figures resumes

On concluding a nomadic sabbatical and updating my approach to systems problems

Forgive me for disappearing the last few months. I’m back, armed with ample motivation to return to writing and illustrating.

Below is a piece summarizing how the months have passed. It contains a personal update and insights since starting this publication on what it means to do research and write about systems problems. This essay and the ones that will follow are more up close and personal than I had originally planned. But perhaps Carl Rogers said it best: “What is most personal is most universal.”

My nomadic lifestyle and 18-month sabbatical comes to a close

At the end of October 2020, my partner and I boxed up our apartments in San Francisco to start a life of picking a new city to live in each month. It began in the Mojave Desert with a plan to continue east into parts of the United States we had never been, but with winter coming we found ourselves changing plans and instead headed south into Mexico. By March of 2022, seventeen months after our journey began, we were pretty much as south as you can possibly go: the spectacular glacial region of Patagonia. Living out of a suitcase for such an extended period was an experience of a lifetime.

One downside of being on the move particularly in foreign countries is that things go wrong, all the time, in such a way that is difficult to anticipate. I had two passports stolen in two separate countries (please contact me if this ever happens to you, I can provide empathy and very specific knowledge). I wasted days of planning as countries and cities understandably made updates and changes in their COVID restrictions. I dealt with the aftermaths of street food and unfiltered water. I had many days without internet because either the power went out or the weather interfered with the weak satellite infrastructure. There was a day I returned from hiking to find our place broken into and my luggage, laptop, and iPad gone. Each month and each mishap made me more patient, more flexible, more resilient.

But some days it made it really hard to make progress on my research, to write thoughtfully, to feel calm enough or grounded enough to do anything creative.

Announcing plans and commitments for a new project is always a risk. The risk is certainly worth taking as it creates an accountability that is vital in personal projects. It psychologically binds you to the promise you’ve made to others. It forces you to push your ideas out into the world, see how they stick, and observe the directions they are naturally pulled. But if the project utilizes a new skill set or way of working (as many do and this one unquestionably did for me), it’s easy to miscalculate what is possible to accomplish in a given period of time.

Publishing the first couple of essays was empowering and insightful. While writing An Emboldened Workforce, I started to see a bigger picture unfolding, the cultural phenomenon that the pandemic had created on how people related to their work. During the holidays, I created an aggressive editorial calendar for the first few months of 2022 with wide-ranging topics like the origins of the American work ethic, the role of unions and organized labor, the trap of consumerism, the promise of remote work, the momentum of ideas like universal basic income and the four day work week.

As January kicked off, I began to examine these topics with a discipline I haven’t really dedicated to much else in my life.

And down the rabbit hole I went

As each week passed, I was consistently stunned by how out of control my research agenda got when I began searching for answers to my questions.

I would sit down Monday morning with my coffee, my enthusiasm, and a primed list of things I wanted to research for the week, only to look up hours later having more on my list than I had started with: additional reports to examine, data to analyze, experts to look up, historical references to validate, opinion pieces to ponder, whole books to read. By the end of the week I had to scroll down several pages just to see the full scope of new work I had assigned myself.

When I started Figures, I genuinely believed I could dive right in to complex, ambiguous topics and come out the other side with a clarity of thought I could communicate broadly simply because I was willing to put in the time. As my understanding of how little I actually knew deepened, I told myself I still didn’t yet have enough ‘expertise’ to write according to the editorial calendar I had built. Months went by and still I published nothing. I drew more into myself and wondered what I had been thinking. I knew this would take time. But how much time?

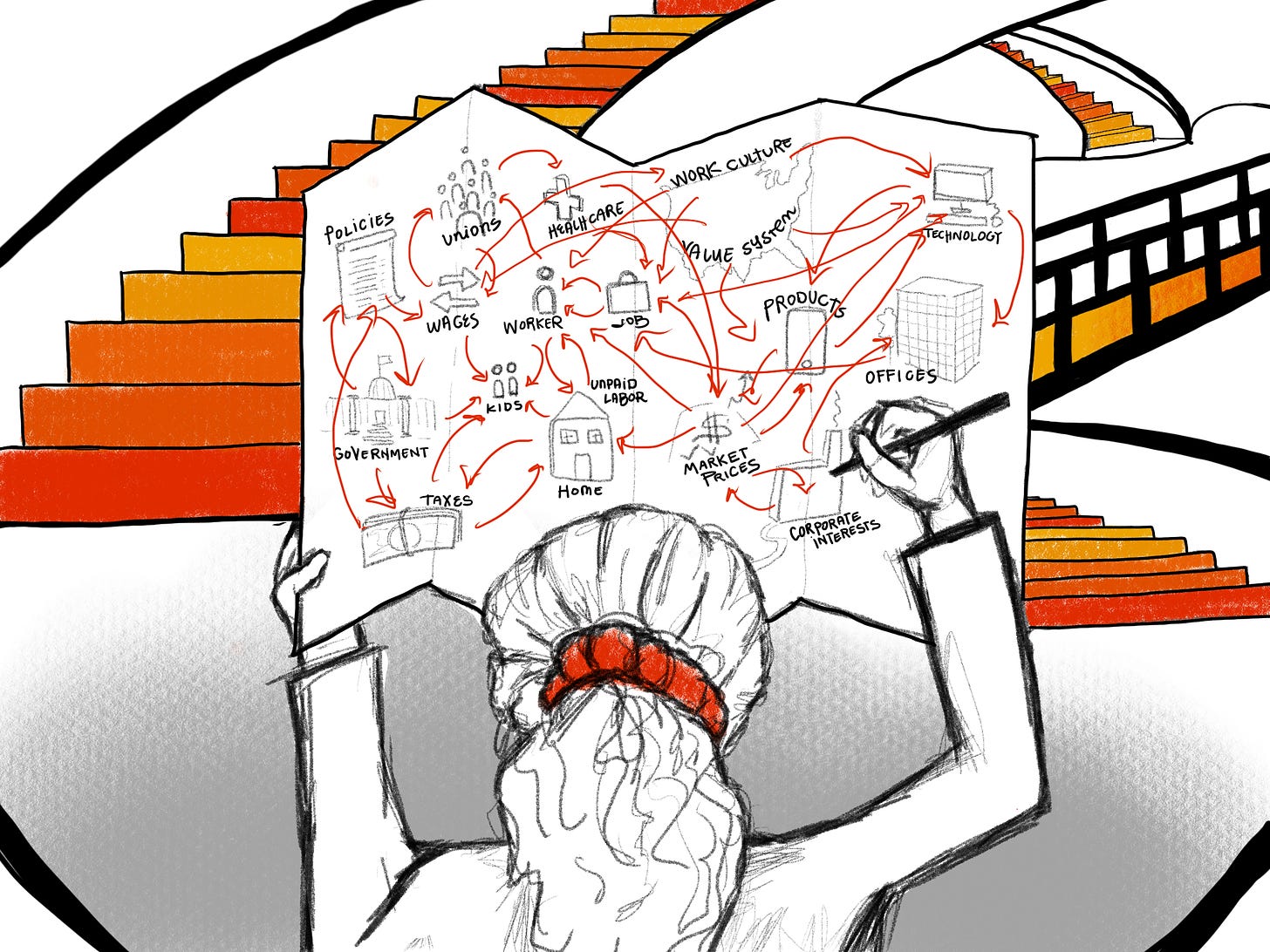

I had managed to become overwhelmed by the very system I was hoping to demystify for others.

My first attempt at recourse was to put some boundaries on the system I was going to write about. But in reality, systems have no real boundaries. By investigating topics related to work, I found myself learning about not only the struggles of working parents, but also the history of capitalism, the line of thinking of economists, and the granularity of passing new policy. The system of work is connected to everything else. Our economy and our government and our livelihoods all depend on it. Our planet and our ecosystems and future generations are affected by it.

"When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe." - John Muir

It’s as if I was trying to create a perfect map of every interconnection that zoomed in and zoomed out endlessly. In hindsight it wasn’t the most realistic of expectations.

I took another step back.

The thing is I didn’t need to become an expert in the system of work, yet I was operating in such a way that one might have thought this was my objective. I was chasing the wrong goal. I went in too deep.

So what was - what is - my objective?

I am after something more fundamental. I want to bridge critical information from different disciplines. I want a more holistic understanding of today’s global challenges because I believe it will unlock new and creative solutions. I want to share a set of tools that can help us see how the parts are connected. I want to expose downstream effects so we can eliminate solutions that are shortsighted.

In short, my objective is to better understand how the world works.

Along the way I want to help you understand how the world works.

As it turns out, there exists a toolset that can help us figure out how the world works.

I’m now collecting mental models

It was like a lightbulb went on. Of course.

There are an infinite number of lenses, models, value systems, and world views in which to look at a system with. Rather than attempting the impossible task of making a single systems map, I can identify the models and maps one particular person or perspective is basing their arguments on. It’s possible that sometimes two expert points of view don’t belong on the same map. It’s possible they draw their maps differently.

Our task then becomes comparing the maps against one another to decide which most closely represent what is actually happening in the real world. We also want to determine which maps put us on a path towards the kind of world we want to live in.

In the previous essay, I shared a podcast episode from The Ezra Klein Show called “The Case Against Loving Your Job”, where guest Sarah Jaffe, author of Work Won’t Love You Back, shared her frustration with hustle culture and the message sold to younger generations that we should love our jobs. She explains that this expectation to be happy at work “is always a demand for emotional work from the worker.” Jaffe continues, “Work, after all, has no feelings. Capitalism cannot love. This new work ethic, in which work is expected to give us something like self-actualization, cannot help but fail.”

Later that week I read dozens of articles published by an organization called 80,000 Hours, the centerpiece of them all was called: “This is your most important decision: Why your career is your biggest opportunity to make a difference, and how you can use it best”. Taking almost the opposite perspective of Jaffe, the organization aligns itself with the ideas of the effective altruism movement and argues that your choice in career is the most critical thing you can do to contribute to the betterment of society.

Who is right? Both are probably valid, and definitely interesting.

The distinctions come from their different mental models on what it means to work and diverse understanding of how the system of work plays out. It remains beneficial for us to examine both in depth, so long as we understand the world views from which they are standing. Donella Meadows in her book Thinking in Systems shares some advice here: “Instead of becoming a champion for one possible explanation or hypothesis or model, collect as many as possible.”

Where might we find these mental models?

Turns out they are everywhere, many of which sit as the fundamental principles of the systems we live in. Farnam Street, a blog founded by Shane Parrish with the popular podcast The Knowledge Project, was originally inspired by investment moguls Warren Buffet and Charlie Munger and their approach to knowledge acquisition. Their team has built an excellent resource for learning about common mental models out there.

The more we expose the models being used to the light of day, so grows the power to examine them carefully, edit them, and redraw them should they be based on flawed or outdated assumptions.

The quality of your thinking depends on the models that are in your head.

- The Great Mental Models, Vol. 1 by Farnam Street

Kate Raworth is doing just that in the world of economics. In her book Doughnut Economics, she outlines some of the most common models used in economics and points out flaws in each of them. By poking holes in the original mental models that support the basis of the modern economy on which so many influential decisions are based on, we might see with new clarity where some of these system problems originate from.

So I am now in the business of collecting and sharing mental models. I have always loved visual tools. I fan girl over great process and decision models (you can take the girl out of IEOR, but you can’t take out the mindset she learned from it). I rely on a variety of management frameworks when I lead teams. I still reference the frameworks I learned in college on human-centered design. This fits right in.

But what about the rabbit holes?

I’ll probably still fall down the rabbits holes from time to time. We all do. Mental models are a toolkit to bring with us when we know we are going in. They can act as guides for navigating complexity, anchors in deciding which details are important. They can help us resurface from the rabbit holes feeling like we gained some new wisdom about the world we live in, so we can better live within it.

A parting note

I’m thrilled to be settling back in California for the foreseeable future. I’m humbled by the lessons learned so far with this project and my hopes for what I want to do with it continue to expand. Thank you for your patience as the publication takes shape and as always I’m grateful for your feedback and comments.

The next few essays will be a reflection on what I learned having taken a long sabbatical. The irony of having researched the world of paid labor while not actively participating in it is not lost on me.

Part 1 will be out next week.