The decision to quit a job without another lined up

Traditionally this has not been considered a good idea

In July of 2020, I was wrestling with whether or not I should leave my job.

By some measures I had “made it” at age 27. I had the enviable job of running an innovation team at a great company in beautiful San Francisco. After seven years there, I had established a strong internal network and mentors. I had a great manager and built a high functioning team of young researchers and engineers. The company stock kept steadily going up. My response to What do you do? at social gatherings elicited eyebrow raises and approving remarks that high achievers crave.

I had what many people might call “a good job”.

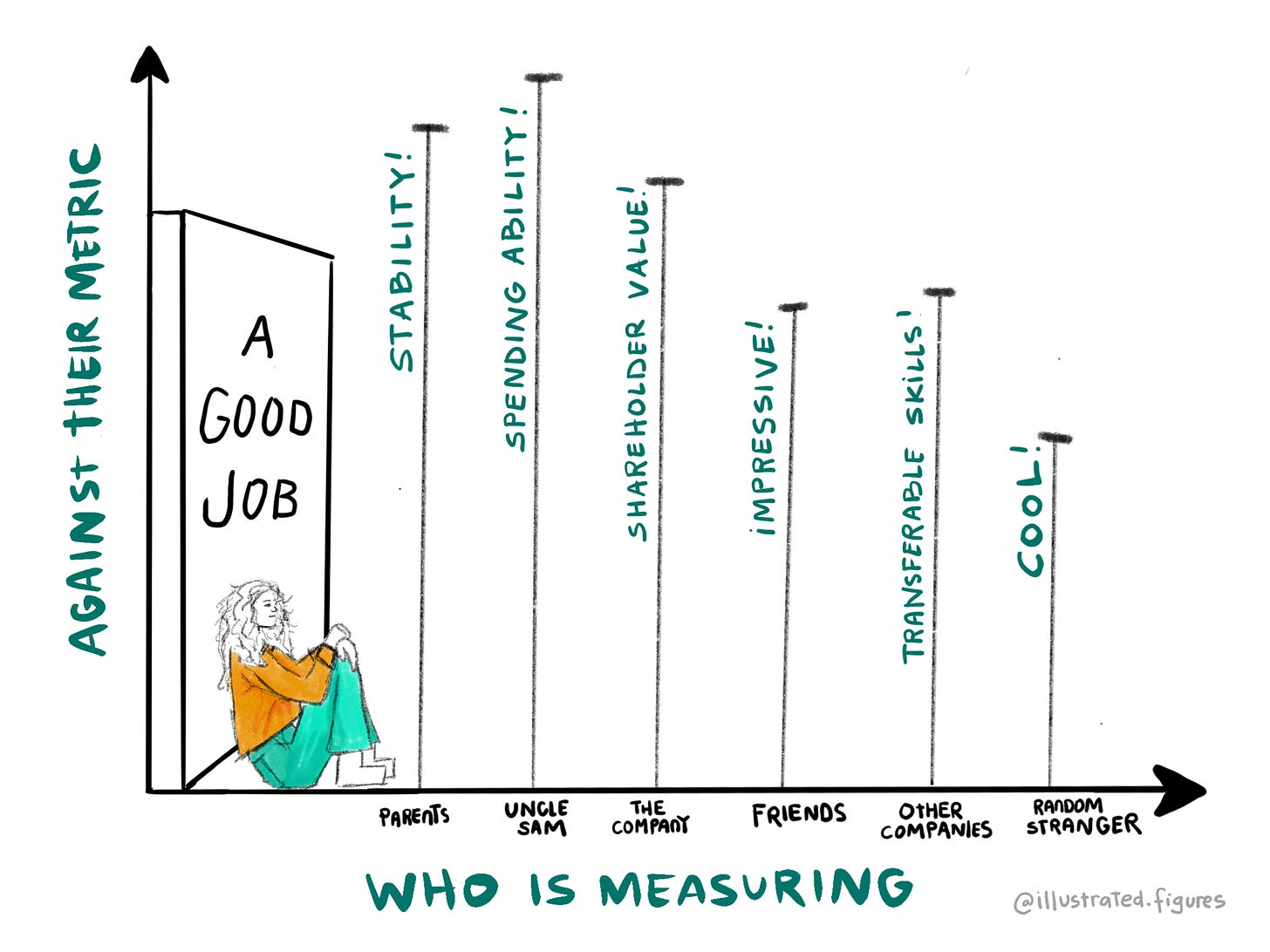

Who is measuring?

Because of this strong execution against society’s measures of success, I was relentless in ignoring my feelings of emptiness. Whenever the question Am I happy at this job? crept up, it was promptly followed by What could be better than this?

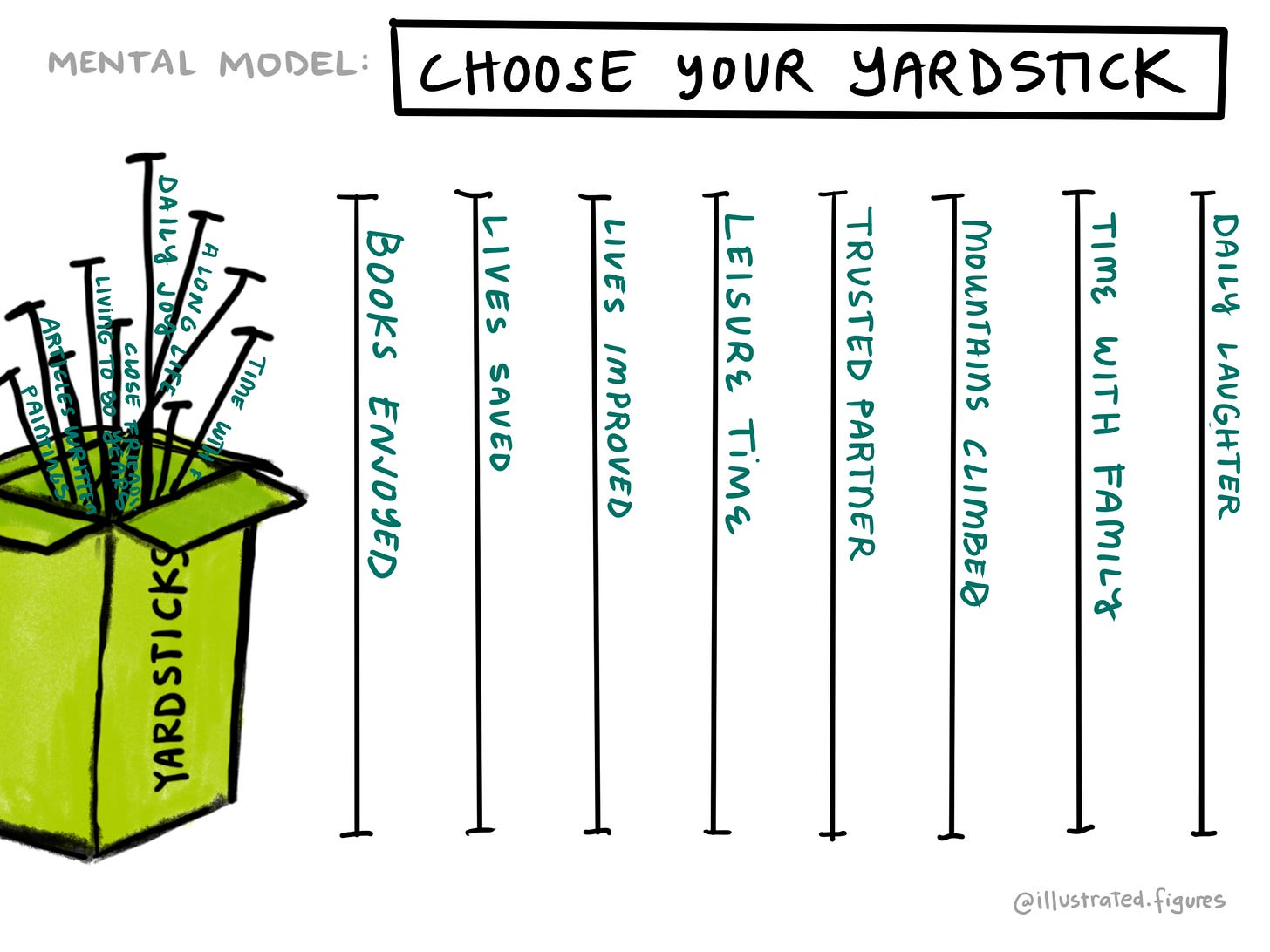

I read Harvard Business Review because I was that kind of employee -cue eye roll- and I was reminded of the article "How will you measure your life?", where late professor Clayton M. Christensen cautions young high-achievers to be mindful of the yardstick they choose to measure success against.

There wasn’t anything explicitly wrong with my job. Of course, there was unnecessary bureaucracy, internal politics, constantly changing priorities due to a lack of long-term thinking, and many other common things that corporate life comes with. But most things were very right.

But as I logged into my daily zoom meetings against the backdrop of an unprecedented global pandemic, a long overdue reckoning with systemic racism, a steadily growing gap in the haves and have-nots, I couldn’t help but notice I was working a job completely insulated from them. These were and are very real, very palpable, long standing global problems. Yet I and so many other sharp minds with “good jobs” were not only not helping solve, we could almost pretend they were someone else’s problem!

The unexpected gift of quarantine

My pre-pandemic life revolved around my calendar and what others expected of me - or my interpretations of what those expectations were. When we went into quarantine this all fell away. Along with my calendar being wiped, so did the oohs and ahs from those approving of ‘the path I was on’, the buzz from feeling loved because I was doing exactly what I thought allowed me to deserve love. All that was left was me and my own voice.

This was mildly infuriating because I wasn’t used to listening to myself. My voice had been so long drowned out by others. I didn’t know what to do with the loud internal debate of how I should feel versus how I did feel.

One thing I did know: I was exhausted.

I was exhausted from the performance I had been putting on of trying to be some version of perfection for so many years.

I've never seen any life transformation that didn't begin with the person in question finally getting tired of their own bullshit.

- Elizabeth Gilbert, Big Magic

I winced when I read this. Amazing how bluntly someone else can put feelings you’ve been unable to find words for.

On the one hand, I was quite amused I had unconsciously put on this whole charade for so many years and achieved very specific things I knew would impress people.

On the other hand, I felt like I had woke up from some weird dream of living a false self, now well into my career and adulthood with an uncertainty of what I wanted to measure my life on, though helping in some way with important global problems seemed like a good place to start. It’s like I looked up for the first time in awhile and realized that despite having an unreasonable appetite to climb mountains, I had been too busy climbing to realize that I was climbing the wrong one.

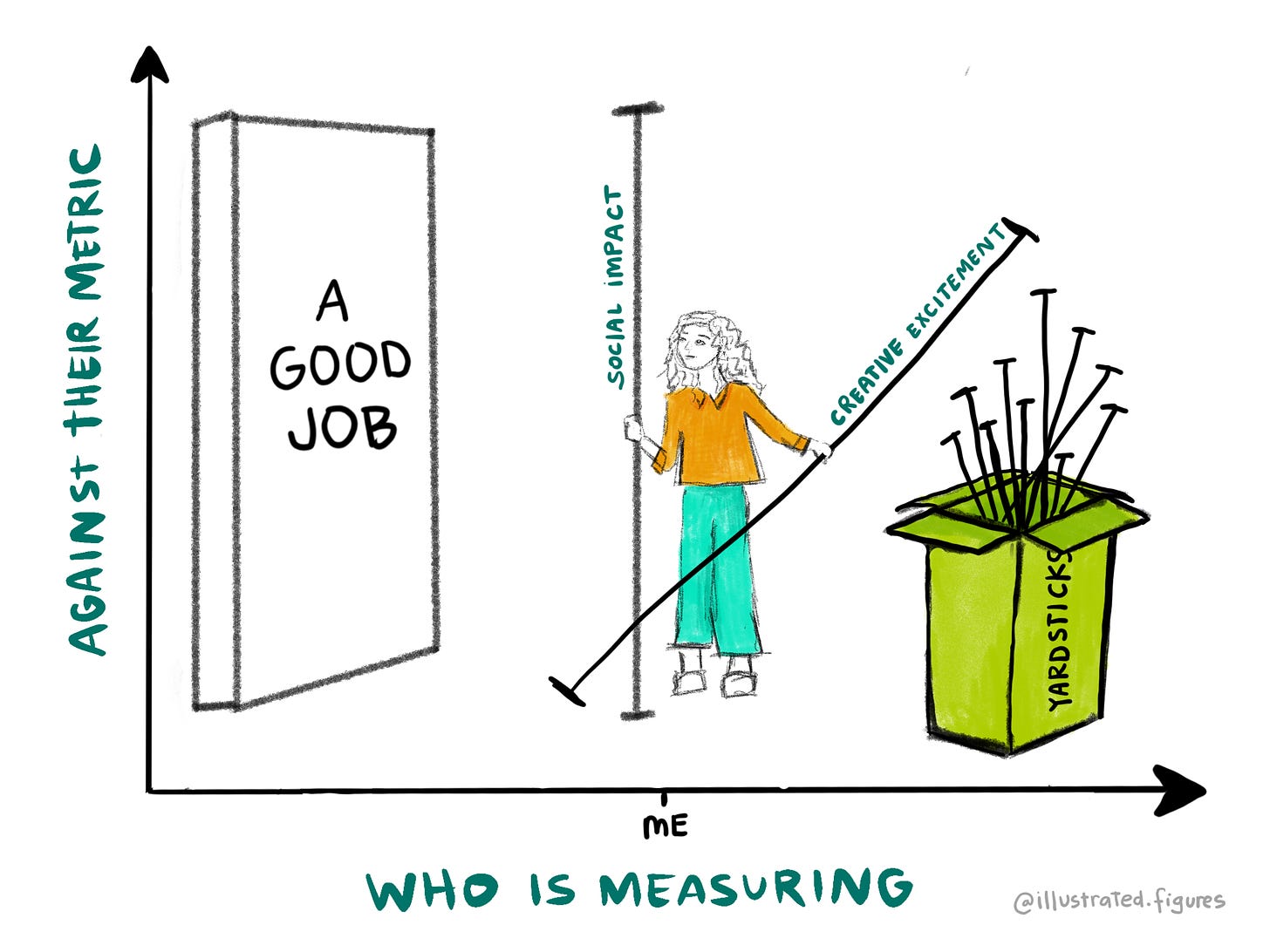

It was time to choose some yardsticks of my own.

Speed isn’t important if we are heading in the wrong direction

The silver lining of the pandemic is that it forced us to change our habits, often downshifting us to a slower paced lifestyle thus enabling us to reexamine the speed in which we were previously living. Maybe for a few, this was frustrating because they loved their life as it was. For most of us, we realized that a lot of the way we were living our lives was completely unsustainable and full of all kinds of unnecessary bullshit.

For me, it was the kind of problems I was working on in my job. Lots of people told me they were important (game-changing!) to the manufacturing industry. But compared to the problems I saw on the news (which I had finally made time to pay attention to), they seemed so tiny and less worthy of dedicating my time to.

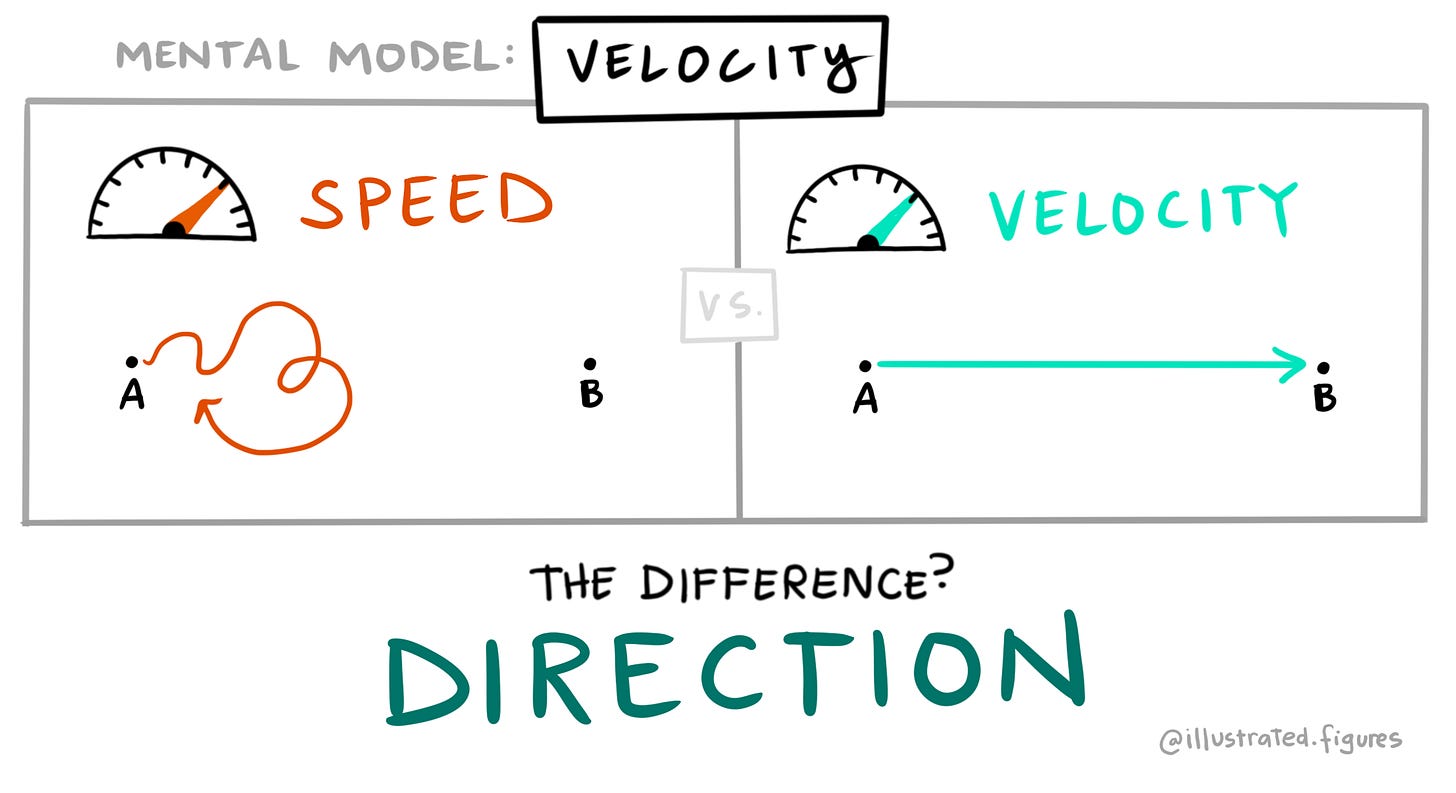

Going back to elementary physics, a useful mental model we can lean on is velocity.

I used this mental model all the time in my job to ensure our research team was headed in the right direction. Without a vision, a north star, I knew much of our efforts would go to waste. We would go farther with less time and resources so long as we had a clear direction for impact.

Yet here I was, not applying the same principles to my own life. I had a lot of speed because I said yes to a lot. I sat on various committees, hosted internal meetups, MC’ed events, all while managing my team and our research projects. I said yes to a lot because I wasn’t sure that I was doing the best work I could be doing. I felt like I could do more, but I only ended up overstretched, yet underutilized.

I was running the risk of heading in the wrong direction for the sake of speed. This is the trap of busyness.

What was the right direction? It’s hard to say. Though I did know more about what was the wrong direction, which could be just as useful.

Inverting to see new possibilities

The pandemic flipped all that was normal upside down, forced us to examine our lives from a totally different angle. It was the perfect environment to utilize inversion, a powerful idea that can allow you to see see alternate solutions, or change the way you think about the problem itself.

There are two approaches we can use to apply inversion:

1. Start by assuming that what you're trying to prove is either true or false, then show what else would have to be true.

2. Instead of aiming directly for your goal, think deeply about what you want to avoid and then see what options are left over

- The Great Mental Models, Vol. 1 by Farnam Street

Inversion requires you to not only identify the forces that support change towards your objective, but also identify those that impede change towards it.

As I considered quitting my job, my mind drifted towards applying to graduate school. But the more I thought about it, grad school isn’t really what I wanted. I wanted permission to carve out time to learn and time to think. Grad school was a vehicle I was hoping to use to reclaim my time back, albeit a very expensive one.

With inversion, I could see that what I wanted to avoid is having other people tell me what success looks like and give myself the time I needed to figure out my own definition for success. Given how drained I felt at the end of each day in my current job, I knew the thing that would impede that the most is staying where I was.

Then I remembered something entrepreneur and author Tim Ferriss had once done:

I decided to make (in my mind) a two-year “Tim Ferriss Fund” that would replace Stanford business school. Stanford GSB isn’t cheap. I rounded it down to $60,000 a year, for a total of $120,000 over two years

For the “Tim Ferriss Fund,” I would aim to intelligently spend $120,000 over two years on angel investing in $10-20,000 chunks, so 6-12 companies in total. The goal of this “business school” would be to learn as much as possible about start-up finance, deal structuring, rapid product design, initiating acquisition conversations, etc. as possible.

Tim Ferriss in “How to Create Your Own Real-World MBA”

In today’s dollars, that same Stanford MBA program would cost $250,000 over two years. I considered the spirit behind what Ferriss did, except for me I wanted to use the time (and much less money) I would have otherwise spent in graduate school and instead build my own program for what I wanted to do with my time.

What would it look like if I took a period of time off, similar to earning a masters degree, to learn as much as I could about myself and the world?

I put in a request to take a couple days of vacation and sat with my journal and my finances. I calculated my average monthly spend over the last year and how much I would save by moving out of the most expensive cities in the world. With a “fund” now built to support myself and a plan to kickoff a cheaper lifestyle outside San Francisco, I logged into zoom the next day and resigned.

What makes a good job?

During my time off, I kept going back to this question of what is “a good job” and why it takes such a toll on us if it falls short. It became the foundation for this series and the answers are more interesting and complicated than I could have ever imagined.

The yardstick mental model is useful because it allows us to be more explicit about the metrics we are judging our lives against. If we don’t take ownership of these metrics, we run the risk of subconsciously using some societal metric based on what the current culture perceives as success. I know, because I did it for so many years.

In reality, what makes a good job is highly personal. There are many schools of thought on this which we will discuss in the coming essays, but they have a common thread: given the choice, better to choose a job based on the kind of life you want to live. A good job should amplify your ability to succeed against your own yardsticks, whether that is about maximizing your ability to save and improve lives, maximizing leisure time to read books and climb mountains, or like me, managing the delicate balance between several.

What are yours?

Dive deeper into these mental models

This week I’m going to be breaking down the mental models of Velocity, Inversion, and Choose Your Yardstick on the Figures Instagram. Give it a follow if you want a deeper understanding and more ideas on how to apply them in your life.

Great post! Each one of us have different "yardsticks" and even within one's career those yardsticks can change with life circumstances.

I just watched this interview with Arthur Brooks and I think you might enjoy it. Especially the parts about high-achievers and pitfalls. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dA5OmuP8vTQ

Amazing, I loved reading this, it was great to understand what was happening when you quit, it was such a shock. I admire your courage and passion to do what you love, to inspire yourself, go be you, you know you will be awesome at it. The yardstick method is great, having gone through major life changes its important to asses yourself by your own standards not other peoples. Be careful and deliberate about those footsteps you follow, because you will end up at their destination, not yours.